A CMYK kódolás, más néven négyszínnyomásos eljárás a sokszorosított nyomtatás során alapszabálynak tekinthető. Minden, ami ebben kódrendszerben létrejön, azt az adott nyomtató képes beolvasni, majd azt festékké transzformálni és így látható formában printté átalakítani. Az egyes csatornákba kódolt számok bizonyos spektrumon belül elhelyezhető színeket jelölnek és minden szín visszafordítva egy adott koordinátarendszerben megjelölhető szám- és betűkódra fordítható.

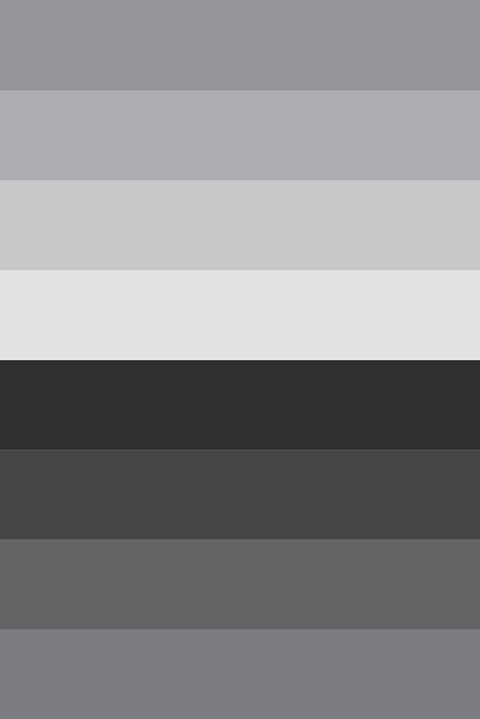

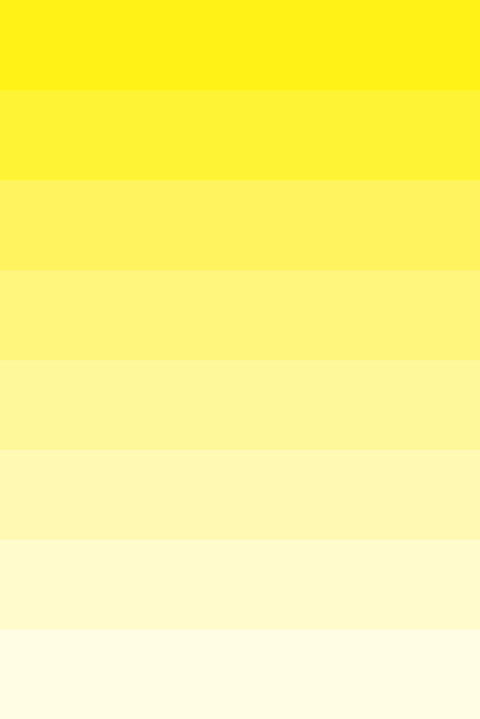

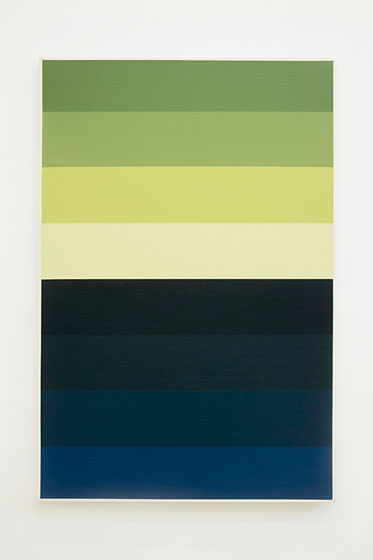

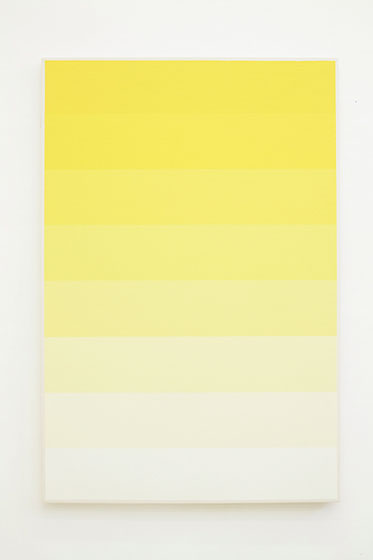

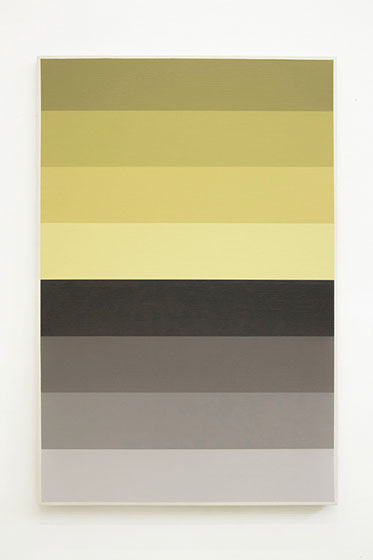

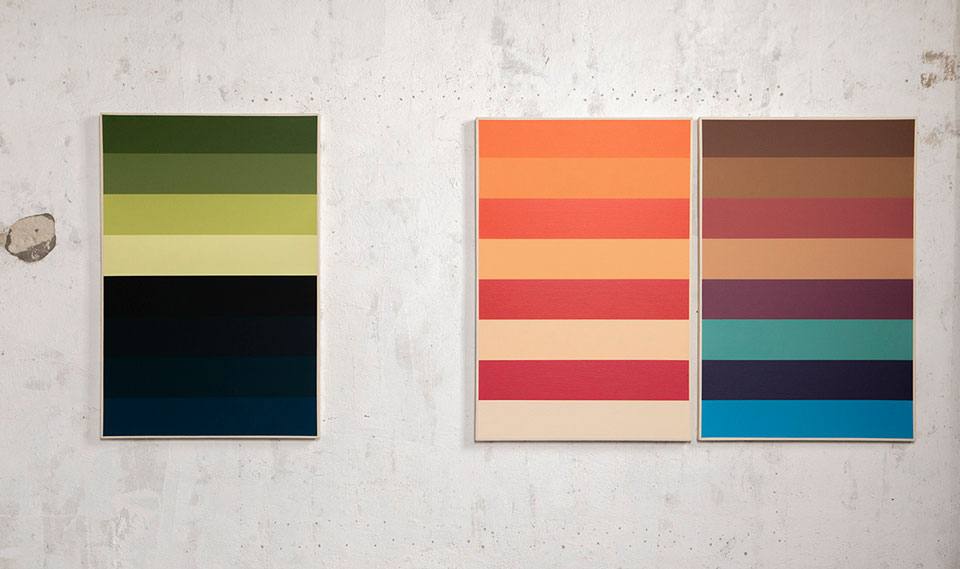

Alapvázként a Photoshop képszerkesztő programon belül egy digitális képet hoztam létre, melyet nyolc, egymással megegyező méretű vízszintes sáv tagol. A program a CMYK színkód szerint képes a négy csatornát különválasztani, majd azok ki- és bekapcsolásának következtében különböző variációkat generálni. Ennek következtében a digitális kép 15 részképpé esik szét –

C; M; Y; K; CM; CY; CK; MY; MK; YK, CMY; CMK; CYK; MYK; CMYK.

Az egyes csatornákon belüli a sávokat nyolc egyenlő részre, 0-100-ig terjedő skálán értelmezhető kódolás szerint rendeztem el, melyeket egy táblázaton belül különböző elvek szerint határoztam meg – pl. csökkenő, növekvő, váltakozó stb. Ezzel mind a négy csatorna egy sajátos belső struktúrát kapott és egymással összekapcsolódva, különböző lehetőségeket és irányokat produkáltak, mígnem az úgynevezett „végső” vagy „eredeti” kép, a CMYK formátum elő nem állt.

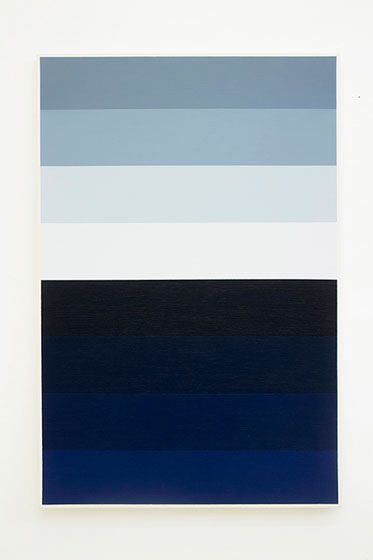

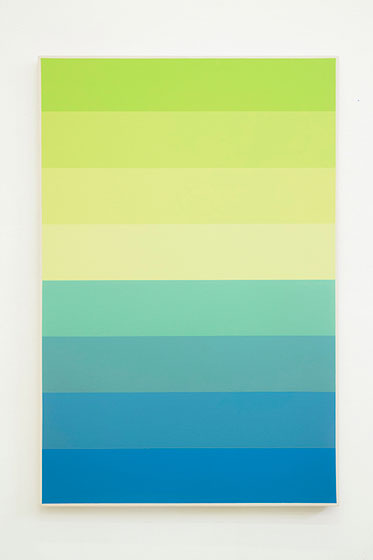

Mind a 15 részképnek elkészítettem egy 120 x 80 cm-es verzióját, magának a digitális formátumnak az analóg típusát. Mindezt a „végső” kép reprodukcióinak fogom fel. Mivel magukat a festményeket egy eleve meghatározott reproduktív struktúra határoz meg, ezért a festői pozíció egyfajta színhelyesség létrehozásában merül ki, mely klasszikusan a reprodukciók összefüggésrendszerében szokott megemlítésre kerülni. Akkor hiteles egy fotóreprodukció, ha megfeleltethetőknek tűnik az a viszony, ami az eredeti viszonyrendszerben jött létre. Itt ennek fordítottjáról beszélhetünk. Míg a nyolc sáv esetében a digitális nyomtató egy kódot olvas be, addig a festmény esetében a festői techné válik nyomtatóvá. A festői szubjektum ezzel háttérbe szorul és feloldódik a megfeleltetésben. E kettősségből fakadóan az egyik oldalon a digitális kép semlegessége, a másik oldalon pedig a festmény egyedisége áll.

C; M; Y; K; CM; CY; CK; MY; MK; YK, CMY; CMK; CYK; MYK; CMYK.

Az egyes csatornákon belüli a sávokat nyolc egyenlő részre, 0-100-ig terjedő skálán értelmezhető kódolás szerint rendeztem el, melyeket egy táblázaton belül különböző elvek szerint határoztam meg – pl. csökkenő, növekvő, váltakozó stb. Ezzel mind a négy csatorna egy sajátos belső struktúrát kapott és egymással összekapcsolódva, különböző lehetőségeket és irányokat produkáltak, mígnem az úgynevezett „végső” vagy „eredeti” kép, a CMYK formátum elő nem állt.

Mind a 15 részképnek elkészítettem egy 120 x 80 cm-es verzióját, magának a digitális formátumnak az analóg típusát. Mindezt a „végső” kép reprodukcióinak fogom fel. Mivel magukat a festményeket egy eleve meghatározott reproduktív struktúra határoz meg, ezért a festői pozíció egyfajta színhelyesség létrehozásában merül ki, mely klasszikusan a reprodukciók összefüggésrendszerében szokott megemlítésre kerülni. Akkor hiteles egy fotóreprodukció, ha megfeleltethetőknek tűnik az a viszony, ami az eredeti viszonyrendszerben jött létre. Itt ennek fordítottjáról beszélhetünk. Míg a nyolc sáv esetében a digitális nyomtató egy kódot olvas be, addig a festmény esetében a festői techné válik nyomtatóvá. A festői szubjektum ezzel háttérbe szorul és feloldódik a megfeleltetésben. E kettősségből fakadóan az egyik oldalon a digitális kép semlegessége, a másik oldalon pedig a festmény egyedisége áll.

CYMK coding, also known as the four-color process, is a basic rule for reproductive printing. Everything what is relevant in this coding can be read by that printer and then transformed into ink and thus converted to print in a visible form. The numbers encoded in each channel represent colors that can be placed within a certain spectrum and vice versa, each color is inverted to a numeric and alphanumeric code in a given coordinate system.

As a basic frame, I created a digital image within the Photoshop program which is divided into eight horizontal bars of the same size. The program is able to separate the four channels according to the CMYK color code and then generate different variations as a result of turning them on and off. Consequently, the digital image falls into 15 sub-frames -

C; M; Y; K; CM; CY; CK; MY; MK; YK, CMY; CMK; CYK; MYK; CMYK.

The bands within each channel were arranged in eight equal parts, coded on a scale of 0 to 100, which were defined in a table according to different principles - e.g. descending, ascending, alternating, etc. Every channel had got a unique structure and combine them together resulted different possibilities and directions, while the so-called „final” or „original” image, the CMYK format did not come up.

I made a 120 x 80 cm version of each of the 15 sub-pictures, the analog type of the digital format itself. I see all this as reproductions of the „final” image. Since the paintings themselves are defined by a predetermined reproductive structure, the position of the painter is based on the creation of a kind of color correctness, which is classically mentioned in the context of reproductions. A photographic reproduction is authentic if the relationship created in the original relationship system seems to be congruent. Here we can talk about the reverse. While in the case of the eight bands the digital printer reads a code, in the case of a painting the painting technician becomes a printer. The picturesque subject is thus pushed into the background and dissolves into correspondence. Due to this duality, the neutrality of the digital image is on one side and the uniqueness of the painting on the other.

C; M; Y; K; CM; CY; CK; MY; MK; YK, CMY; CMK; CYK; MYK; CMYK.

The bands within each channel were arranged in eight equal parts, coded on a scale of 0 to 100, which were defined in a table according to different principles - e.g. descending, ascending, alternating, etc. Every channel had got a unique structure and combine them together resulted different possibilities and directions, while the so-called „final” or „original” image, the CMYK format did not come up.

I made a 120 x 80 cm version of each of the 15 sub-pictures, the analog type of the digital format itself. I see all this as reproductions of the „final” image. Since the paintings themselves are defined by a predetermined reproductive structure, the position of the painter is based on the creation of a kind of color correctness, which is classically mentioned in the context of reproductions. A photographic reproduction is authentic if the relationship created in the original relationship system seems to be congruent. Here we can talk about the reverse. While in the case of the eight bands the digital printer reads a code, in the case of a painting the painting technician becomes a printer. The picturesque subject is thus pushed into the background and dissolves into correspondence. Due to this duality, the neutrality of the digital image is on one side and the uniqueness of the painting on the other.