←

szöveg

text

Photography: Gyuricza Mátyás

Align & Distribution

Virtuális

A termelés gépezetében a hálózatosság és a digitalizálás elengedhetetlen tényezőkké váltak. Egyaránt képezik a fennálló rend alapját és céljait. Az idő és tér dimenziói egybekapcsolódnak és egy integráns egészként adatokként, mérhető entitásokként, és digitalizált információkként újra értelmet nyernek, ezzel átalakítva végletekig a társadalmi lét különböző tartományait. Minden egyfajta folyamatos cirkulációban érhető tetten, ahol a meghatározott pontok és a közöttük kialakult kapcsolatok folyamatos újraértelmezése és (újra)kalibrálása a meghatározó. Egyfajta konstans mozgás, ahol a történéseknek mérete, kiterjedése és preferenciája van. E kapcsolódások révén a globális világban az egyik oldalon egy olyan kép rajzolható fel, melyben mindenki osztozik a totális instrumentalizáltság utópikus víziójában. A másik oldalon pedig egy fragmentált világ romjai között mozgunk és a válság közepette megfigyeltként, konszenzusok nélkül próbáljuk megérteni a különböző mozgásirányokat és narratívákat.

E paradoxonon alapuló szituációban linkek, referenciák és statisztikai adatok együttese alkotja a kontextust, melyben az elsődleges szempont az információ terjedésének flexibilitása, a gazdasági teljesítmény maximalizációja és e teljesítményben fellelhető anomáliák szisztematikus redukciója, felszámolása. Követve Manuel Castells A hálózati társadalom kialakulása című könyvének alaptézisét, minél inkább hálózatos egy társadalom, annál fejlettebbnek számít, és minél inkább független egységek, autonóm egyének, vagy intézmények alkotják, annál inkább kell szembesülni a lassúság, a fejletlenség vagy a cselekvésképtelenség kritikai és egyben ellentmondásos fogalmaival. „Az áramlások ereje elsőbbséget élvez az erők áramlásával szemben”.

A gráfszerű elrendezések, az adatvizualizáció, az infografika és a diagram képi dimenziójában, fogalmi rendszerében és forradalmi hevületében a létező egy mérhető és összehasonlítható entitásban éri el csúcspontját, és egyfajta vektorként új értelmet nyer. A vektor egyrészről matematikai fogalom, másrészről társadalmi dimenzióval is felruházható, és valaminek az irányát jelöli, semmint helyzetét és pozícióját. A vizsgált test és testek végtelen absztrakción esnek át, és nem mint létezőként, hanem meta-objektumként és mint mozgásban lévő tárgyként fogalmazódnak meg.

A vektorok szöveges megfogalmazása képként leírható és a vektor képi dimenziói, formai keretrendszere szintén átformálható más nyelvi szintekre, hogy egy komplex kódként beolvasható legyen a termelés különböző részegységei számára. Folyamatosan múlt és jövő között lebegnek.

A kép, amit ezáltal kapunk, nem egy kimerevített egység lesz, nem egy autonóm fogalom, hanem egy folyamatos mozgásban lévő, helyzetét és kontextusát folyamatosan változtató formává alakul és lokalitása, identitása fluiddá, fragmentálttá válik. Sőt, a vektor ennél differenciáltabb, csakis abban az esetben jöhet létre, ha a fluiditás már létezik, és kettő vagy több összehasonlítható objektumon keresztül már felállítható és feltételezhető. Ha nincs kapcsolat, a fogalom szertefoszlik és darabokra esik. Egy olyan képlékeny koordináta-rendszerről beszélhetünk, melyben a társadalmi intézményrendszertől kezdve az egyén létének megértéséig, a történelem homályosságától a tiszta ész megvalósulásáig, a nomád létezés-formáktól a technokrata és technooptimista hozzáállásokig és a művészet politikai létezőként való értelmezésétől az esztétikai létezéséig különböző adatok, dokumentumok, számok és információk adnak segítséget, vagy épp teszik zajossá a különböző fogalmak integritását és valószerűségét. Látszólag semmi sem eléggé lecsatlakoztatott és független a globalizmuson belül és homogenizáló mechanizmusaihoz képest, és semmi sem elég összegző a lokális kontextusok kritikai aspektusaihoz és szempontjaihoz viszonyítva. Mégis adott egy sűrűsödési pont, ami az egyik oldalon partikuláris, a másik oldalon univerzális.

Paul Virilio Az eltűnés esztétikája című híres szövegében több példán és ellentmondáson keresztül érzékelteti a hatalom, annak módszerei és a technológia működésének kapcsolatából kialakuló piknolepsziát, azaz a megfigyelés és a megfigyelhetőség pontjai között megfogható üresség létét és fontosságát, az elidegenedés milyenségét. Az önmagunkon kívülre kerülés, és a saját létünk vektoriális tényezőként való felfogásának összefüggésrendszerében Wilhelm Reichtól idéz, aki egyik megszólalásában arra figyelmeztet, hogy a hatalmi diskurzusban „Nem testetek van, testek vagytok!”. Mindezt Virilio úgy fordítja át, hogy eközben egy paradigmaváltást is érzékeltet, ahol a vektorialitás spektrumában „Nem sebességetek van, sebesség vagytok!”.

Aktuális

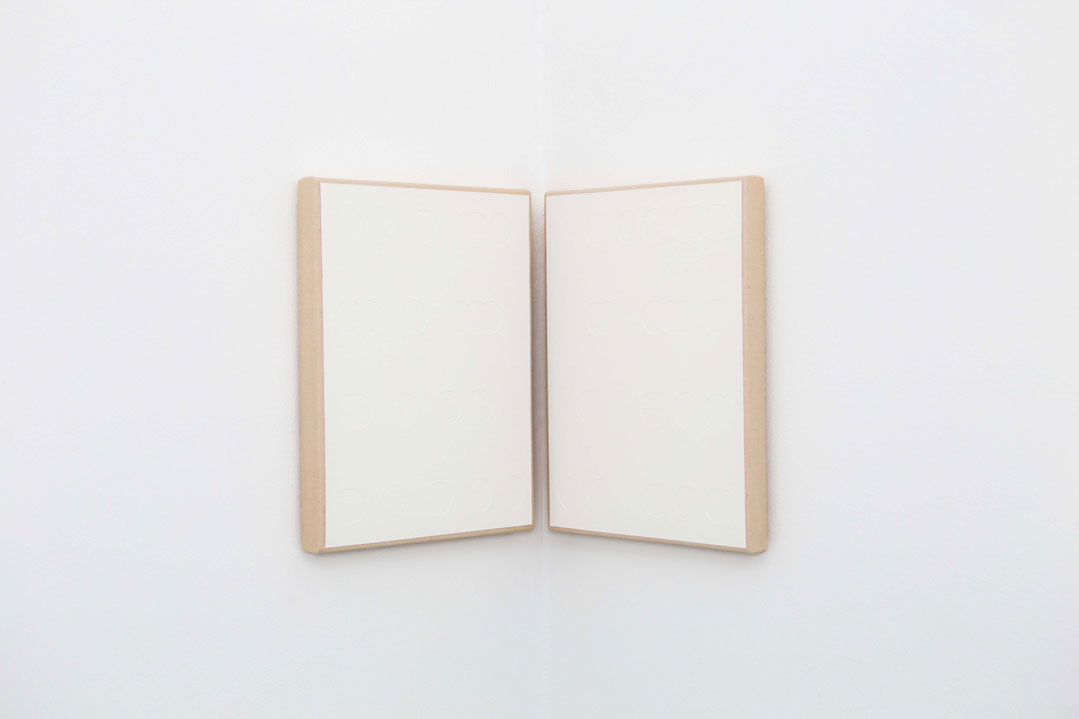

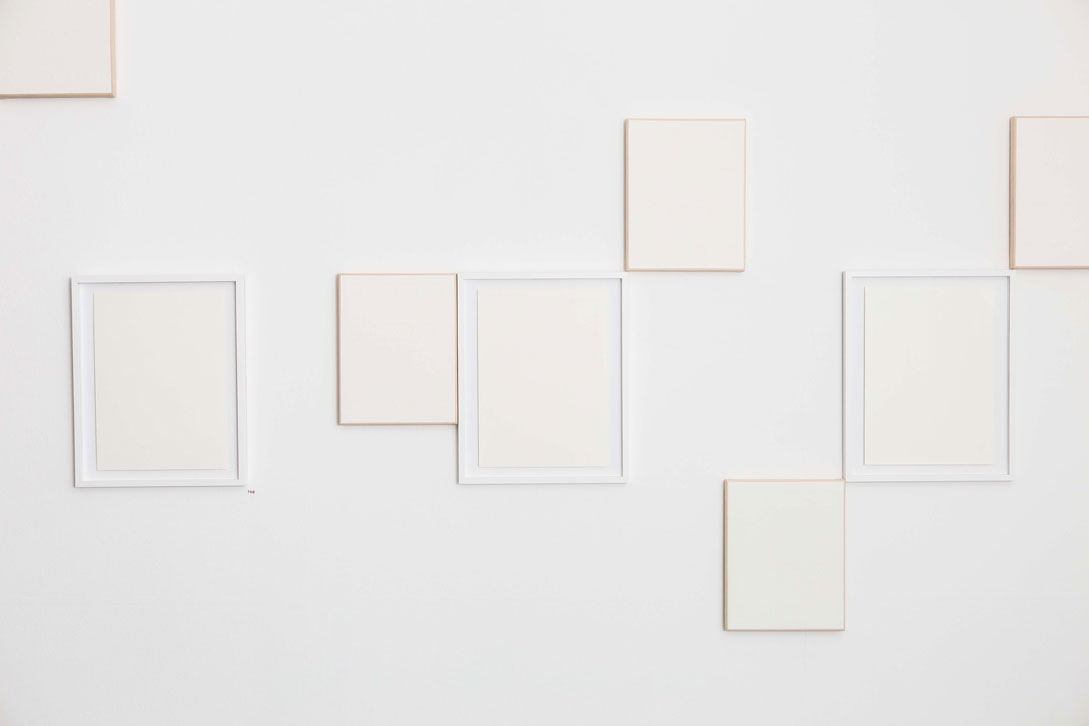

A kiállítás fókuszában a hálózat, a vektorialitás, valamint a digitális képszerkesztés fogalmi keresztmetszete áll. Egy festészeti kontextuson belül vizsgálva a kérdést, célja a közöttük lévő illékony kapcsolat, a referenciapontok közötti irányok és kiterjesztett dimenziók megértése. A három, egybekapcsolódó munka révén a bennük megjelenő algoritmikusság, a közöttük lévő tér és relációs kapcsolat külsővé tétele tekinthető fontosnak. Nem a tárgyakon, mint egyedi gesztusokon, hanem azok feltételezett, valamint elengedhetetlen összemérhetőségén, reflexióján és a vektorialitás alapélményként való bemutatásán van a hangsúly: a festészet instrumentális és konceptuális tulajdonságainak felkutatásán.

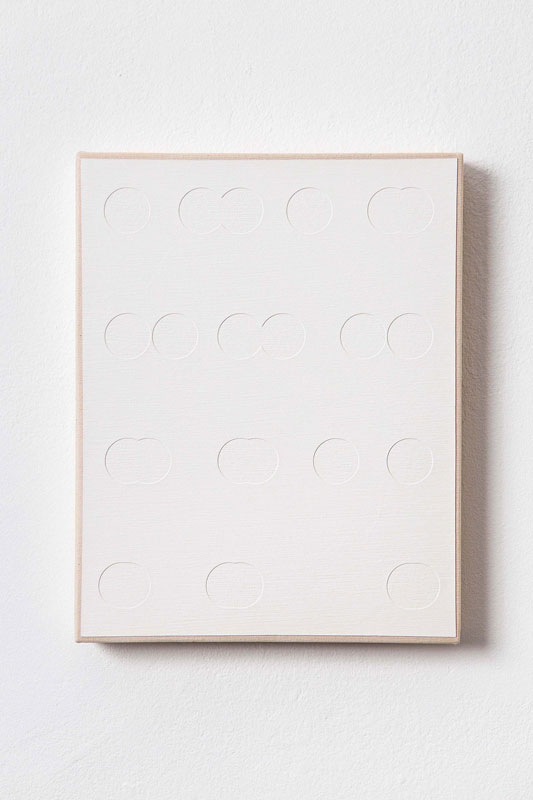

E fogalmi kereten belül az ,align’ és a ‚distribution’ az Adobe Illustrator adta eszközöket jelölik, melyek a programon belül kijelölt vektor-objektumok mozgatásában segítenek. Definíció szerint, ezen objektumok bizonyos referenciapontok mentén kezelhetők, így egy adott objektum szélei, a rajztáblán kialakított rögzítési pontok, vagy akár egy általunk megjelölt kulcsobjektum mentén is. Ennek következtében a kiállításon bemutatott képtárgyak és feliratok áttételesen vektor-objektumként definiálhatók, és élhelyezkedésük leköveti a meghatározott referenciapontok jellegét: a kiállítótér dimenzióit, valamint a program adta párhuzamok tartományát. A bekeretezett metszet-képek horizontálisan, egy vonalban, a festmények pedig a tér különböző kulcsobjektumaihoz, térbeli váltópontokhoz vannak igazítva, ezzel képezve átmenetet a visszafejthetőség és az egység képzete közé.

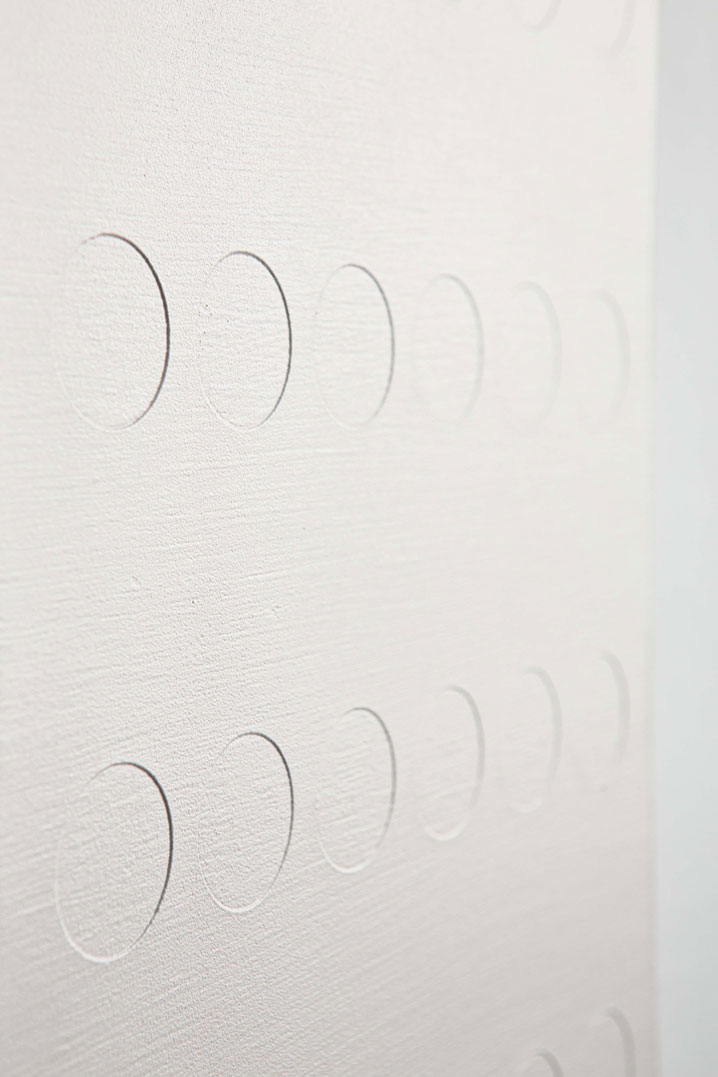

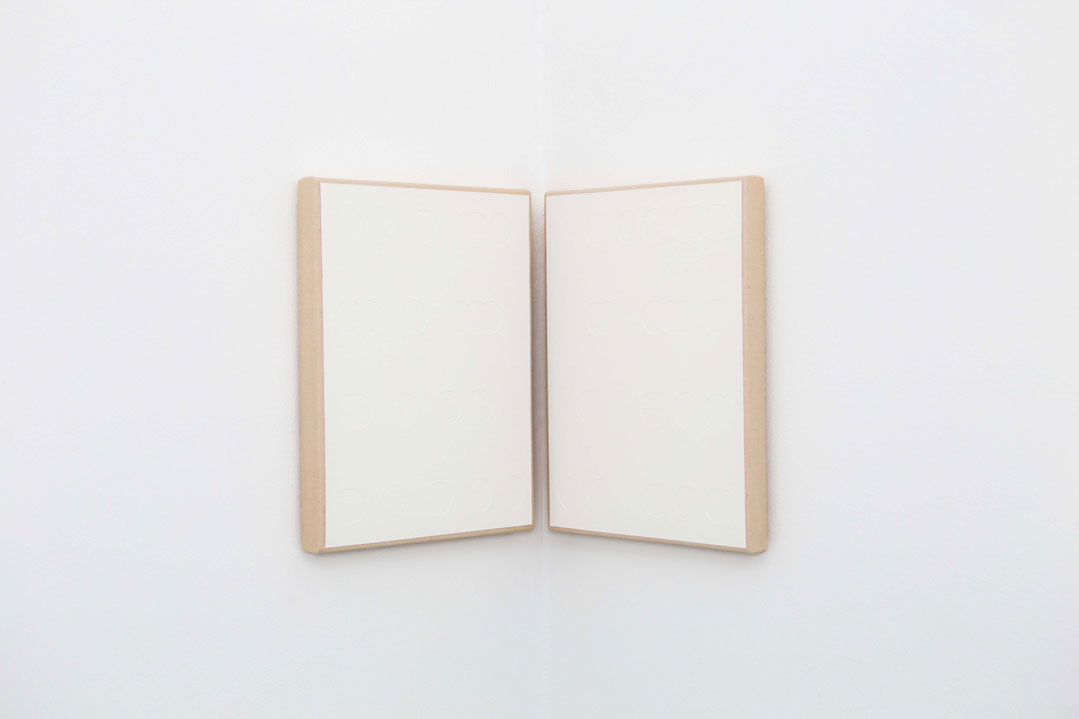

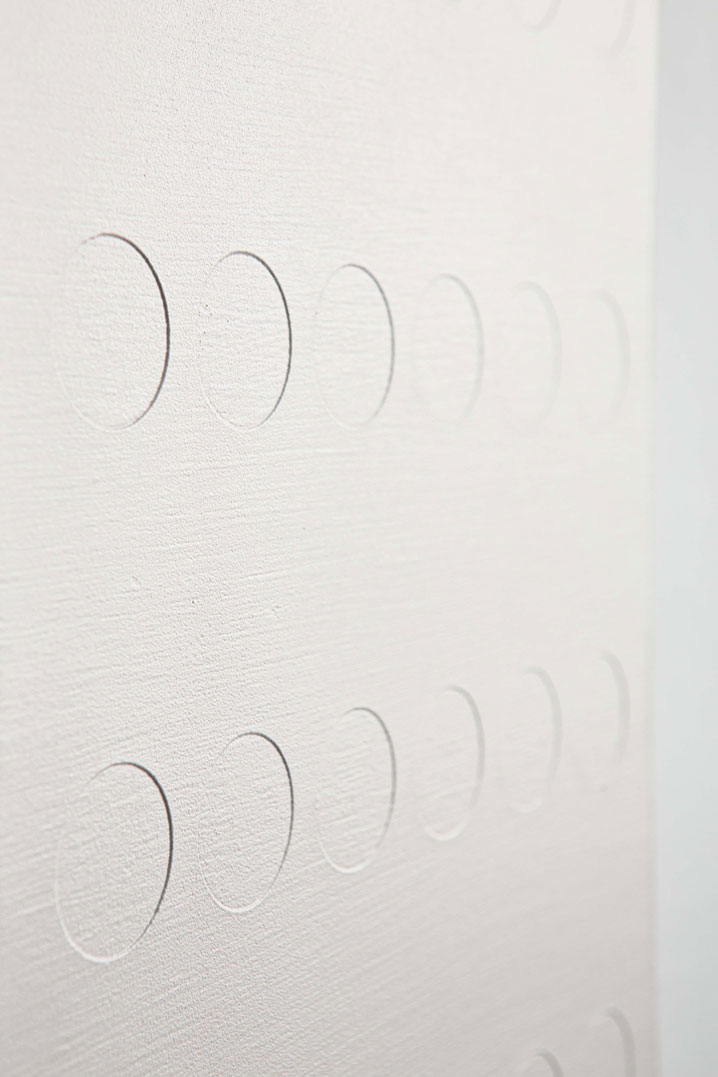

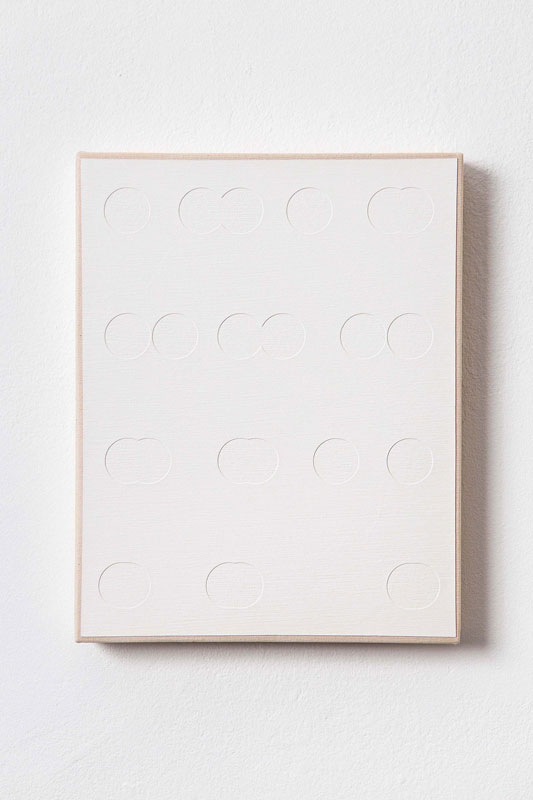

A digitális képszerkesztés során a vektor-objektum egyfajta regisztrációs jel, ami többnyire a tömörítés mikéntjét, a forma-, irány- és szögtartás lehetőségeit és kvalitásait jelenti. Míg egy vektoros forma látszólag korlátlan minőségben nagyítható, addig egy pixeles kép ezen tulajdonságokkal nem rendelkezik és nem is rendelkezhet. Egyrészről egy vizuálisan és formailag meghatározható egység, melynek belső tere a ‚fill’, kerete pedig a ‚stroke’ fogalmával egyezik. Másrészről pedig egy kód, ‚outline’, melyet különböző termelési eszközök már képesek beolvasni és értelmezni. A nyers papír, valamint a vásznak fehér színe a munkaterület ‚default’, azaz alapértelmezett helyzetét hivatottak betölteni. A vásznak szélén megfigyelhető rózsaszín vonal pedig a kép szélére és egyben a vektorként értelmezett festmény ‚stroke’ fogalmára vonatkozik. A papírokon megfigyelhető, fóliavágó géppel létrehozott finom vágások és a festményeken látható körvonalak a regisztrációs jellel azonosak, csak az egyik esetben alig látható jelekként, a másik esetben pedig térbeli eltolódásokként fogalmazódnak meg.

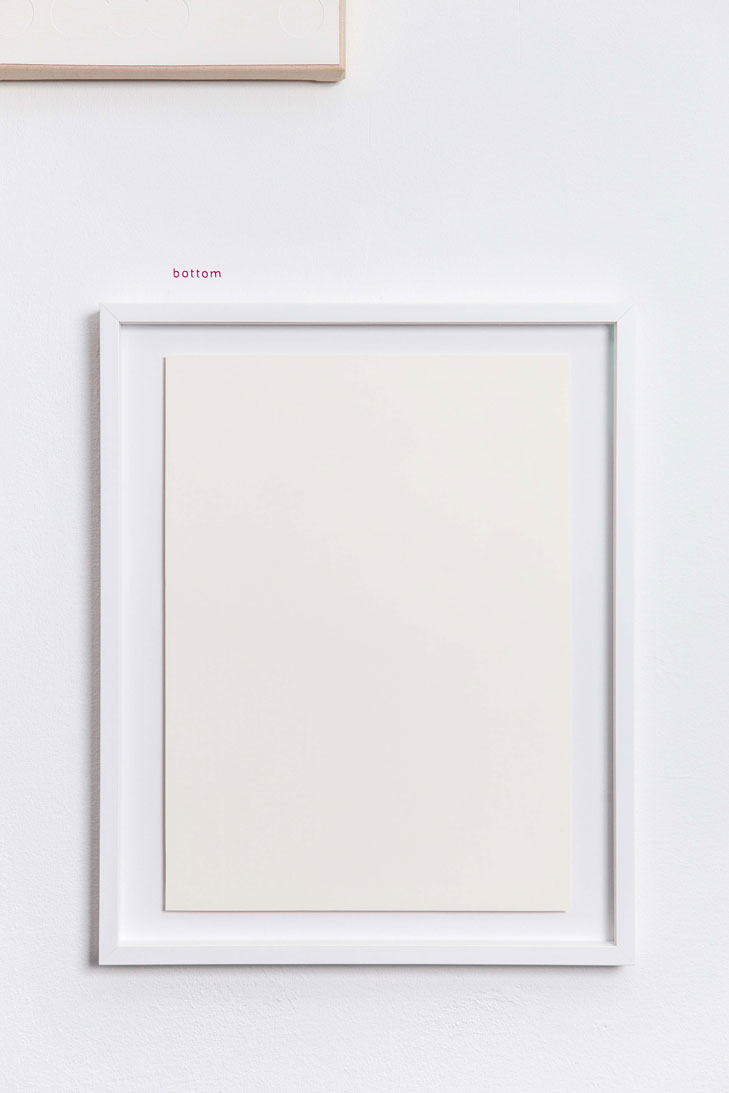

Ha programon belül egy objektum a munkatér különböző sarokpontjaihoz ér - középre, a kép széléhez, vagy a lekötött tartományokhoz -, úgy egy rózsaszín vonallal és felirattal jelzi ennek létrejöttét. Ez az úgynevezett ‚smart guide’. A program szerint ezek a tartományok azokat az alapvető vektorokat jelölik, amelyek egy kétdimenziós térben meghatározhatók, így a diszpozíciók a következők: ‚center’, ‚top’, ‚bottom’, ‚left’, ‚right’. Követni és alkalmazni lehet őket, de nem minden esetben szükségszerű. Azonban ezek helyzetjelölő fogalmak, és nem egy adott irányt jelölnek, miközben de facto magukba foglalják a megtett utat is. A térben elhelyezett feliratok nem az adott pontok helyét, hanem egy előre megadott haladási irányt jelölnek, és egy következő referenciapontra vonatkoznak. Egyfajta ‚smart guide’-ként funkcionálnak, ami a kiállítás egészét mint egy előre megszabott, követhető vektorpályát határoz meg.

A képtárgyak alapváza egy 6 oszlopból és 4 sorból álló, körökből felépülő struktúra. Ez tekinthető úgymond az alapértelmezett képnek. A 64 festmény esetében minden egyes oszlop, a 16 bekeretezett munka esetében pedig minden egyes sor permutációja adja ki a részképeket. A permutáció az adott kijelölésekre vonatkozik, melyben a kijelölt oszlop vagy sor a ‚distribution’ eszköz algoritmikus parancsa révén más helyre kerül. A munkák címei egyrészről egy sorszámot, másrészről pedig a kijelölt és elmozgatott tartományokat jelölik. A kijelölésekből fakadó transzformáció révén az egyes verziókon minden kör egy sajátos belső struktúrát kapott, ezáltal részlegesen megtartva eredeti pozíciójukat, feloldódva tárgyként és képként egyaránt egy új állapotban, a folyamatos mozgathatóság, visszafejthetőség és cirkuláció spektrumában.

Virtual

Networking and digitalisation have become indispensable factors in the system of production. They are both the base and the superstructure of the existing order. The dimensions of time and space are intertwined and reinterpreted as an integral whole as data, measurable entities and digitised information, transforming to the extreme the different domains of social existence. Everything can be understood in a kind of continuous circulation, where the constant reinterpretation and (re)calibration of the defined points and the relations between them is decisive. A kind of constant movement, where events have a size, an extent and a preference. Through these connections, a picture is drawn on one side of the global world in which everyone shares a utopian vision of total instrumentalization. On the other side, we move among the ruins of a fragmented world and, in the midst of crisis, we try to understand the different directions of movement and narratives as observers without consensus.

In this paradoxical situation, the context is a set of links, references and statistical data, in which the primary concern is the flexibility of information flow, the maximisation of economic growth and the systematic reduction and elimination of anomalies in this performance. Following the basic thesis of Manuel Castells’s The Rise of the Network Society, the more networked a society is, the more advanced it is considered to be, and the more independent units, autonomous individuals or institutions it is made up of, the more it is confronted with critical and contradictory notions of slowness, underdevelopment or incapacity. „The power of flows takes precedence over the flow of power”.

In the pictorial dimension, conceptual system and revolutionary fervour of graphical layouts, data visualisation, infographics and diagrams, the existent culminates in a measurable and comparable entity and takes on a new meaning as a kind of vector.

A vector is a mathematical concept on the one hand, but it can also have a social dimension, and it marks the direction of something rather than its position and location. The body and bodies under consideration undergo an infinite abstraction and are not conceived as existing, but as meta-objects and objects in motion. The textual formulation of the vectors can be described as an image and the pictorial dimensions and formal framework of the vector can also be transformed into other levels of language to be read as a complex code for the different parts and levels of production. They are constantly floating between past and future.

The image that is thus obtained does not become a frozen entity, an autonomous concept, but a form in constant movement, constantly changing its position and context, and its locality and identity become fluid and fragmented. Moreover, the vector is more differentiated than this, it can only come into being if fluidity already exists and can be established and assumed through two or more comparable objects. If there is no connection, the concept disintegrates and falls apart. We can speak of an alterable coordinate system in which various data, documents, figures and information, from the social institutional system to the understanding of the existence of the individual, from the obscurity of history to the realisation of pure reason, from nomadic forms of existence to technocratic and techno-optimistic attitudes and from the understanding of art as a political being to its aesthetic existence, help or even make noisy the integrity and plausibility of the various concepts. Apparently, nothing is sufficiently disconnected and independent from the globalism and its homogenizing mechanisms, and nothing is sufficiently summarizing in relation to the critical aspects and perspectives of local contexts. Yet a point of densification is given, particular on one side and universal on the other.

Paul Virilio, in his famous text The Aesthetics of Disappearance, uses a series of examples and contradictions to illustrate the picnolepsy that arises from the relationship between power, its methods and the operation of technology, that is, the existence and importance of the void that can be grasped between the points of observation and observability, the nature of alienation. In the context of being outside of ourselves, and of seeing our own existence as a vector, he quotes Wilhelm Reich, who in one of his speeches warns that in the discourse of power „You don’t have bodies, you are bodies!”. Virilio translates all this in such a way that he also detects a paradigm shift, where in the spectrum of vectoriality „You do not have speed, you are speed!”.

The exhibition focuses on the conceptual cross-section of network, vectoriality and digital image editing. By exploring the issue within a painterly context, it aims to understand the volatile relationship between them, the directions and extended dimensions between these references. Through the three compound works, the algorithmicity that emerges within this framework, the externalisation of the spatial and relational connections between the objects, is considered important. The emphasis is not on objects as individual gestures, but on their presumed as well as indispensable inter-comparability, their reflection and the presentation of vectoriality as a basic experience: an exploration of the instrumental and conceptual properties of painting.

Actual

Within this conceptual framework, ‚align’ and ‚distribution’ refer to the tools provided by Adobe Illustrator to assist in the movement of vector objects selected within the program. By definition, these objects can be manipulated along certain reference points, such as the edges of an object, anchor points on the workspace, or even a key object that we have specified. As a consequence, the artworks and inscriptions presented in the exhibition can be defined as vector objects and their final positions follow the nature of the reference points defined: the dimensions of the exhibition space and the range of parallels given by the program. The framed engraved images are horizontally aligned in a single line, and the paintings are aligned to different key objects of the space, spatial points of change, thus forming a transition between the notion of regression and the notion of unity.

In digital image editing, the vector object is a kind of registration mark, which mostly refers to the way of compression, the possibilities and qualities of shape, direction and angle. While a vector shape can be enlarged with apparently unlimited quality, a pixel image does not and cannot have these qualities. On the one hand, it is a visually and formally definable entity, with an interior space corresponding to the concept of ‚fill’ and a frame corresponding to the concept of ‚stroke’. On the other hand, it is a code, an ‚outline’, which can be read and interpreted by various machines of production. The white colour of the raw paper and the canvas are intended to fill the ‚default’ position of the workspace. The pink line on the edge of the canvas refers to the edge of the image and also to the ‚stroke’ concept of the painting as a vector. The engraves on the paper, created by a foil cutting machine, and the outlines in the paintings are identical to the registration mark, but in one case they are barely visible marks and in the other case they are spatial shifts.

Within the program, when an object reaches different corners of the workspace - the centre, the edge of the image, or the bound regions - a pink line and a caption indicate that this has occurred. This is called as ‚smart guide’. According to the program, these ranges represent the basic vectors that can be defined in a two-dimensional space, so the dispositions are ‚centre’, ‚top’, ‚bottom’, ‚left’, ‚right’. They can be followed and applied, but are not always necessary. However, they are positional concepts and do not indicate a specific direction, while de facto they also include the path taken. The signs in the exhibition space do not indicate the location of a point, but a predetermined direction of travel, and refer to a subsequent reference point. They function as a kind of ‚smart guide’, defining the exhibition as a whole as a predetermined vector trajectory to be followed.

The basic framework of the pictorial objects is a structure of 6 columns and 4 rows of circles. This can be considered as the default image. The permutation of each column for the 64 paintings and each row for the 16 framed works gives the sub-images. The permutation refers to specific selections, in which the selected column or row is moved to a different location by an algorithmic command of the ‚distribution’ tool. The titels of the the works represent a row number on the one hand, and the selected and moved ranges on the other. Through the transformation resulting from the assignments, each circle in each version has been given a specific internal structure, thus partially retaining its original position, dissolving as both object and image in a new state, in a spectrum of continuous mobility, decomposability and circulation.